Aciclovir was seen as the start of a new era in antiviral therapy, as it is extremely selective and low in cytotoxicity. Pharmacologist Gertrude B. Elion was awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize in Medicine, partly for the development of acyclovir.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

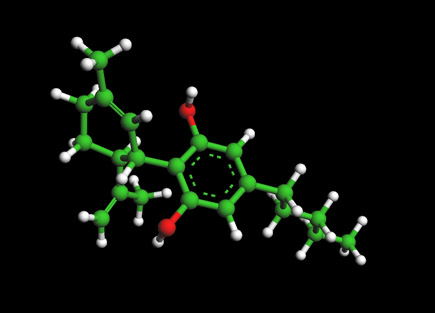

Acylovir differs from previous nucleoside analogues in that it contains only a partial nucleoside structure: the sugar ring is replaced by an open-chain structure. It is selectively converted into acyclo-guanosine monophosphate (acyclo-GMP) by viral thymidine kinase, which is far more effective (3000 times) in phosphorylation than cellular thymidine kinase. Subsequently, the monophosphate form is further phosphorylated into the active triphosphate form, acyclo-guanosine triphosphate (acyclo-GTP), by cellular kinases. Acyclo-GTP is a very potent inhibitor of viral DNA polymerase; it has approximately 100 times greater affinity for viral than cellular polymerase. As a substrate, acyclo-GMP is incorporated into viral DNA, resulting in chain termination. It has also been shown that viral enzymes cannot remove acyclo-GMP from the chain, which results in inhibition of further activity of DNA polymerase. Acyclo-GTP is fairly rapidly metabolised within the cell, possibly by cellular phosphatases.

In sum, aciclovir can be considered a prodrug: it is administered in an inactive (or less active form) and is metabolised into a more active species after administration.

Microbiology

Acylovir is active against most species in the herpesvirus family. In descending order of activity:[1]. Herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-1) ; Herpes simplex virus type II (HSV-2) ; Varicella zoster virus (VZV) ; Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) ;Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Activity is predominantly against HSV, and to a lesser extent VZV. It is only of limited efficacy against EBV and CMV. It is inactive against latent viruses in nerve ganglia.

To date, resistance to aciclovir has not been clinically significant. Mechanisms of resistance in HSV include deficient viral thymidine kinase; and mutations to viral thymidine kinase and/or DNA polymerase, altering substrate sensitivity.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

Acylovir is poorly water soluble and has poor oral bioavailability (10-20%), hence intravenous administration is necessary if high concentrations are required. When orally administered, peak plasma concentration occurs after 1-2 hours. Acylovir has a high distribution rate, only 30% is protein-bound in plasma. The elimination half-life of aciclovir is approximately 3 hours. It is renally excreted, partly by glomerular filtration and partly by tubular secretion.

Indications

Acylovir is indicated for the treatment of HSV and VZV infections, including:[3]

- Genital herpes simplex (treatment and prophylaxis)

- Herpes simplex labialis (cold sores)

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Acute chickenpox in immunocompromised patients

- Herpes simplex encephalitis

- Acute mucocutaneous HSV infections in immunocompromised patients

- Herpes simplex keratitis (ocular herpes)

- Herpes simplex blepharitis (not to be mistaken with ocular herpes)

- Bell's Palsy

It has been claimed that the evidence for the effectiveness of topically applied cream for recurrent labial outbreaks is weak.[4] Likewise oral therapy for episodes is inappropriate for most non-immunocompromised patients, whilst there is evidence for oral prophylactic role in preventing recurrences.[5]

Dosage forms

Aciclovir is commonly marketed as tablets (200 mg, 400 mg and 800 mg), topical cream (5%), intravenous injection (25 mg/mL) and ophthalmic ointment (3%). Cream preparations are used primarily for labial herpes simplex. The intravenous injection is used when high concentrations of aciclovir are required. The ophthalmic ointment preparation is only used for herpes simplex keratitis.

Topical therapy

Aciclovir topical cream is commonly associated with: dry or flaking skin and/or transient stinging/burning sensations. Infrequent adverse effects include erythema and/or itch.[3]

When applied to the eye, aciclovir is commonly associated with transient mild stinging. Infrequently ophthalmic aciclovir is associated with superficial punctate keratitis and/or allergic reactions.[3]

Toxicity

Since aciclovir can be incorporated also into the cellular DNA, it is a chromosome mutagen, therefore, its use should be avoided during pregnancy. However it has not been shown to cause any teratogenic nor carcinogenic effects. The acute toxicity (LD50) of aciclovir when given orally is greater than 1 g/kg, due to the low oral bioavailability. Single cases have been reported, where extremely high (up to 80 mg/kg) doses have been accidentally given intravenously without causing any major adverse effects.

Footnotes

- O'Brien JJ, Campoli-Richards DM. Acyclovir. An updated review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 1989;37(3):233-309. PMID 2653790

- Sweetman S, editor. Martindale: The complete drug reference. 34th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004. ISBN 0-85369-550-4

- Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- Graham Worrall (6 Jul 1996). "Evidence for efficacy of topical acyclovir in recurrent herpes labialis is weak". BMJ 313: 46.​- Letter

- Graham Worrall (6 Jan 1996). "Acyclovir in recurrent herpes labialis". BMJ 312: 6.​ - Editorial

Further reading

- Harvey Stewart C. in Remington’s Pharmaceutical Sciences 18th edition: (ed. Gennard, Alfonso R.) Mack Publishing Company, 1990. ISBN 0-912734-04-3.

- Huovinen P., Valtonen V. in Kliininen Farmakologia (ed. Neuvonen et al.). Kandidaattikustannus Oy, 1994. ISBN 951-8951-09-8.

- Périgaud C., Gosselin G., Imbach J. -L.: Nucleoside analogues as chemotherapeutic agents: a review. Nucleosides and nucleotides 1992; 11(2-4)

- Rang H.P., Dale M.M., Ritter J.M.: Pharmacology, 3rd edition. Pearson Professional Ltd, 1995. 2003 (5th) edition ISBN 0-443-07145-4; 2001 (4th) edition ISBN 0-443-06574-8; 1990 edition ISBN 0-443-03407-9.