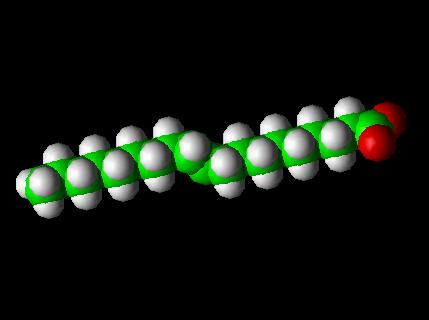

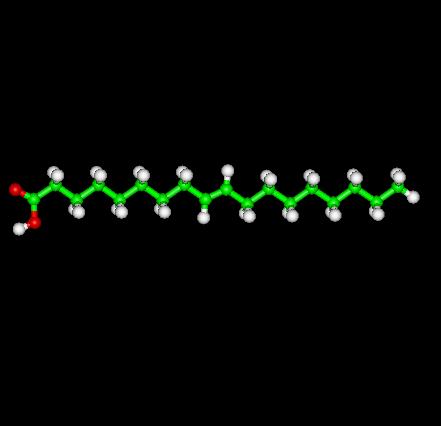

Trans Fatty Acid Molecule

Trans Fatty Acid Molecule -- Elaidic Acid-- Space Fill Model

To View the Trans Fatty Acid Molecule in 3D using Jsmol

What are Trans Fatty Acids?

A trans fatty acid (commonly shortened to trans fat) is an unsaturated fatty acid molecule that contains a trans double bond between carbon atoms, which makes the molecule kinked. Research suggests a correlation between diets high in trans fats and diseases like atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. The National Academy of Sciences recommended in 2002 that dietary intake of trans fatty acids be minimized.

Trans Oleic Acid shown above is a linear molecule as compared to Oleic Acid's monounsaturated cis form found that occurs naturally in various animal and vegetable fats and oils.

Trans fats in food

Though a negligible amount of trans fats are found naturally (in mostly animal foods), they are primarily formed during the manufacture of processed foods (see below for details). In unprocessed foods, most unsaturated bonds in fatty acids are in the cis configuration.

Trans fat from partially hydrogenated vegetable oils has displaced natural solid fats and liquid oils in many areas.

Partial hydrogenation increases the shelf life and flavor stability of foods containing these fats. Partialy hydrogenation also raises the melting point, producing a semi-solid material, which is much more desirable for use in baking than liquid oils. Partially hydrogenated vegetable oils are much less expensive than the fats originally favored by bakers, such as butter or lard. Because they are not derived from animals, there are fewer objections to their use.

Snack foods, fried foods, baked goods, salad dressings, and other processed foods are therefore likely to contain it, as are vegetable shortenings and margarines. Laboratory analysis alone can determine the amount.

Though some newer variants differ, most margarines have much more trans fat than butter. Advocates say that the trans fats of margarine are healthier than the saturated fats of butter. Some say the theory that saturated fats are unhealthy is wrong anyway. See the saturated fats page for details.

Chemistry of trans fats

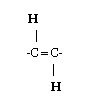

Trans fatty acids are made when manufacturers add hydrogen to vegetable oil -- in a process described as partial hydrogenation. If the hydrogenation process were allowed to go to completion, there would be no trans fatty acids left, but the resulting material would be too solid for practical use. Usually the hydrogen atoms at a double bond in a natural fatty acid are positioned on the same side of the carbon chain. However, partial hydrogenation reconfigures most of the double bonds that do not become chemically saturated, so that the hydrogen atoms end up on different sides of the chain. This type of configuration is called trans (which means "across" in Latin). The structure of a trans unsaturated chemical bond is shown in the diagram.

Biochemistry of trans fats

Trans fat behaves like saturated fat by raising low-density lipoprotein (LDL or "bad cholesterol") that increases the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). It also decreases levels of HDL in the blood, this is the "good" lipoprotein that helps remove cholesterol from arteries.

Some reports have suggested that trans fats may be worse for the body than saturated fats; in fact, some studies that have incriminated saturated fat made no distinction between the two.

Labelling of trans fats

Consumers in the United States can find out if a food contains trans fat by looking at the ingredient list on the food label. If the ingredient list includes the words "shortening," "partially hydrogenated vegetable oil" or "hydrogenated vegetable oil," the food contains trans fat. Because ingredients are listed in descending order of predominance, smaller amounts are present when the ingredient is close to the end of the list.

Because of public awareness of the health risks of saturated fat, food companies marketed trans fat as a healthy monounsaturated fat. Whereas actual monounsaturated oils are now thought to be healthier, trans fats (which take on many of the properties of saturated fats) are much worse.

On July 9, 2003, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a regulation requiring manufacturers to list trans fatty acids, or trans fat, on the Nutrition Facts panel of foods and some dietary supplements. This will appear below the listing of saturated fat content, which is already required to be listed.

Food manufacturers have until Jan. 1, 2006, to list trans fat on the nutrition label of items sold in the United States. The FDA estimates that by three years after that date, trans fat labeling will have prevented from 600 to 1,200 cases of coronary heart disease and 250 to 500 deaths each year. This benefit is expected to result from consumers choosing alternative foods lower in trans fatty acids as well as manufacturers reducing the amount of trans fatty acids in their products.

Canada's food regulator, Health Canada, started mandatory Nutrition Facts labels in 2003 (for gradual introduction over several years); from the beginning, they have required the listing of the amount of trans fats in the food described.

Trans fats in the news

In May 2003, a U.S. non-profit corporation filed a lawsuit against the food manufacturer Kraft Foods in an attempt to get Kraft to remove the trans fats from the Oreo cookie. The lawsuit was withdrawn when Kraft agreed to work on ways to find a substitute for the trans fat in the Oreo.

This suit was very effective at bringing the trans fat controversy to public attention.

External References

- Talking About Trans Fat: What You Need to Know --FDA

- Trans Fats -- The Facts -CDC

- FDA information on trans fats (http://www.fda.gov/oc/initiatives/transfat/)

- FDA HHS press release (http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2003pres/20030709.html)

- Enig MG, Atal S, Keeney M, Sampugna J. Isomeric trans fatty acids in the U.S. diet.

- http://www.bantransfat.com/

- http://www.cnn.com/2003/LAW/05/14/oreo.suit/