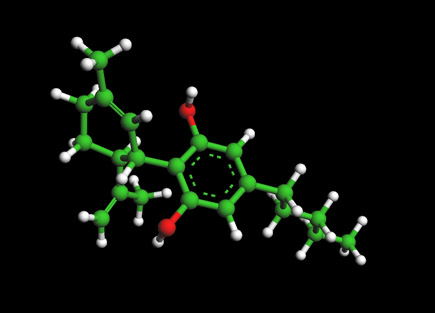

Tamiflu Molecule - Oseltamivir

Ball and Stick Model for Tamiflu Molecule -Oseltamivir

To View the Tamiflu Molecule in 3D --->>in 3D with Jsmol

Four drugs have been approved to fight the Flu: Amantadine (Symmetrel); Oseltamivir (Tamiflu); Rimantadine (Flumadine) ; and Zanamivir (Relenza)

Tamiflu -- Oseltamivir is an antiviral drug that is used in the treatment and prophylaxis of both Influenzavirus A and Influenzavirus B. Like zanamivir, oseltamivir is a neuraminidase inhibitor. It acts as a transition-state analogue inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase, preventing progeny virions from emerging from infected cells.

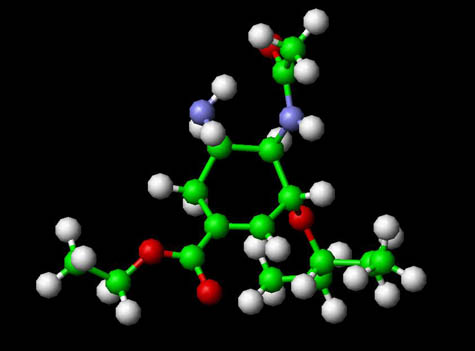

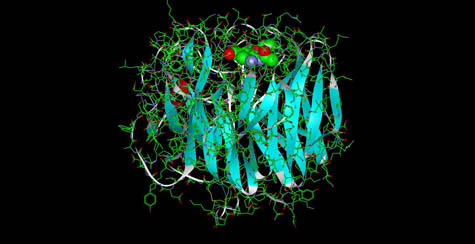

The Oseltamivir Molecule bound to Neuramindase

For 3-D Structure

Oseltamivir was the first orally active neuraminidase inhibitor commercially developed. It is a prodrug, which is hydrolysed hepatically to the active metabolite, the free carboxylate of oseltamivir (GS4071). It was developed by Gilead Sciences and is currently marketed by Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche) under the trade name Tamiflu. In Japan, it is marketed by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., which is more than 50% owned by Roche. Oseltamivir is generally available by prescription only. However since Tamiflu was originally extracted from Chinese Star Anise, a traditional remedy for colds and flu many are now choosing the Star Anise extracts.

Roche estimates that 50 million people have been treated with oseltamivir[1]. The majority of these have been in Japan, where an estimated 35 million have been treated [2].

With increasing fears about the potential for a new influenza pandemic, oseltamivir has received substantial media attention. Governments, corporations, and even some private individuals are stockpiling the drug. Production is currently sufficient to meet the demand for seasonal influenza and for government stockpiling. It is possible that shortages could re-emerge in the event of an actual influenza pandemic.

Pharmacology -- Clinical use

Oseltamivir is indicated for the treatment of infections due to influenza A and B virus in people at least one year of age, and prevention of influenza in people at least one year and older. The usual adult dosage for treatment of influenza is 75 mg twice daily for 5 days, beginning within 2 days of the appearance of symptoms and with decreased doses for children and patients with renal impairment. Oseltamivir may be given as a preventive measure either during a community outbreak or following close contact with an infected individual. Standard prophylactic dosage is 75 mg once daily for patients aged 13 and older, which has been shown to be safe and effective for up to six weeks. [3] [4]

Use and dosage for avian influenza

After following WHO protocols in treating 41 victims of the H5N1 bird flu virus (19% of the world-wide cases of bird flu reported to date), Nguyen Tuong Van, MD, who runs the intensive care unit of the Center for Tropical Diseases in Hanoi, Vietnam concluded that Tamiflu, the drug most widely stockpiled around the world to combat a potential bird flu pandemic, is "useless" [5]. According to this article, the WHO confirmed Van's experience stating that Tamiflu has not been "widely successful in human patients", but speculated the drug has not been administered until late in the disease in many Asian countries.

The standard recommended dose incompletely suppresses viral replication in at least some patients with H5N1 avian influenza, increasing the risk of viral resistance and rendering therapy less effective [6]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that higher doses and longer durations of therapy should be used for treatment of patients with the H5N1 virus [6] [7].

Clinical trials for an increased dosage were set to begin in by May 2007. All avian influenza cases in Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam will be inducted into the trial. The trial will also iclude 100 cases of severe seasonal influenza from each of those countries, plus the United States. Half of cases will receive the current standard dosage, and half will receive a double dosage, but for the standard length of time.[8] [9]. Chokephaibulkit et al recommend the use of oseltamivir for children with avian influenza, based on experience with one patient [10].

Co-administration with probenecid

It has been suggested that co-administration of oseltamivir with probenecid could extend the limited supply of oseltamivir. Probenecid reduces renal excretion of the active metabolite of oseltamivir. One study showed that 500 mg of probenecid given every six hours doubled both the peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the half-life of oseltamivir, increasing overall systemic exposure (AUC) by 2.5-fold [11]. Although the evidence for this interaction comes from a study by Roche, it was publicised only in October 2005 by a doctor who had reviewed the data [12]. Probenecid was used in similar fashion during World War II to extend limited supplies of penicillin. It is still used to increase penicillin concentrations in serious infections.

Adverse effects

Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with oseltamivir therapy include: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and headache. Rare ADRs include: hepatitis and elevated liver enzymes, rash, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. [4]. Various other ADRs have been reported in postmarketing surveillance including: toxic epidermal necrolysis, cardiac arrhythmia, seizure, confusion, aggravation of diabetes, and haemorrhagic colitis.[citation needed]

Neurological effects

There are concerns that oseltamivir may cause dangerous psychological side effects in some people. This stems from cases in Japan, where the drug is most heavily prescribed. Concern has focused on teenagers, but problems have also been reported in children and adults.

In March 2007, Japan's Health Ministry warned that oseltamivir should not be given to children aged 10 to 19. [5] The Ministry had previously decided, in May 2004, to change the literature accompanying oseltamivir to include neurological and psychological disorders as possible adverse effects, including: impaired consciousness, abnormal behavior, and hallucinations.

According to Japan's Health Ministry, between 2004 and March 2007, fifteen people aged 10 to 19 have been injured or killed by jumps or fallen from buildings after taking oseltamivir, and one 17-year-old died after he jumped in front of a truck.[6][7][8] A renewed investigation of the Japanese data was completed in April 2007. It found that 128 patients had been reported to behave abnormally after taking oseltamivir since 2001. Forty-three of them were under 10 years old, 57 patients were aged 10 to 19, and 28 patients were aged 20 or over. Eight people, including five teens and three adults, had died as a result.[9] (For more on Japan, also see: [13] [14])

In November 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) amended the warning label to include the possible side effects of delirium, hallucinations, or other related behavior.[15] This went further than the FDA's previous pronouncement, from a year before, that there was insufficient evidence to claim a causal link between oseltamivir use and the deaths of 12 Japanese children (only two were from neurological problems, although more have died since then). [16]The change to a more cautionary stance was attributed to 103 new reports that the FDA received of delirium, hallucinations and other unusual psychiatric behavior, mostly involving Japanese patients, received between August 29, 2005 and July 6, 2006. This was an increase from the 126 similar cases logged between the drug's approval in 1999 and August 2005. [10]

In October 2006, Shumpei Yokota, a professor of pediatrics at Yokahama City University, released the results of research involving around 2,800 children which found no difference in the behavior between those who took oseltamivir and those who did not. A media source notes that Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. (which produces Tamiflu in Japan) gave Yokota's department 10 million yen ($85,000) over five years.[11][12]. Roche points out that Tamiflu has been used to treat 50 million people since 1999, and states that influenza may itself cause psychological problems.[13][14]. In March 2007, the European Medicines Agency said that the benefits of oseltamivir outweighed the costs, but that it would closely monitor reports from Japan. [15]. In April 2007, South Korea issued a safety warning against prescribing tamiflu to teenagers except in special cases.[16]

Mode of action

Oseltamivir is a neuramnidase inhibitor. By blocking the activity of the neuraminidase, Oseltamivir prevents new viral particles from being released by infected cells.

Resistance

As with other antivirals, resistance to the agent was expected with widespread use of oseltamivir, though the emergence of resistant viruses was expected to be less frequent than with amantadine or rimantadine. The resistance rate reported during clinical trials up to July 2004 was 0.33% in adults, 4.0% in children, and 1.26% overall. Mutations conferring resistance are single amino acid residue substitutions in the neuraminidase enzyme [7]. Mutant H3N2 influenza A virus isolates resistant to oseltamivir were found in 18% of a group of 50 Japanese children treated with oseltamivir [17]. This rate was similar to another study where resistant isolates of H1N1 influenza virus were found in 16.3% of another cohort of Japanese children [7]. Several explanations were proposed by the authors of the studies for the higher-than-expected resistance rate detected. First, children typically have a longer infection period, giving a longer time for resistance to develop. Second, Kiso et al.claim to have used more rigorous detection techniques than previous studies[17]. Third, the dosage regimen in Japan is different from that of other nations, and some children may have been given a suboptimal dosage of oseltamivir.

High-level resistance has been detected in one girl suffering from H5N1 avian influenza in Vietnam. She was being treated with oseltamivir at time of detection [18][19].de Jong et al. (2005) describe resistance development in two more Vietnamese patients suffering from H5N1, and compare their cases with six others. They suggest that the emergence of a resistant strain may be associated with a patient's clinical deterioration. They also note that the recommended dosage of oseltamivir does not always completely suppress viral replication, a situation that could favor the emergence of resistant strains. Moscona (2005) gives a good overview of the resistance issue, and says that personal stockpiles of Tamiflu could lead to under-dosage and thus the emergence of resistant strains of H5N1 [20].

Resistance is of concern in the scenario of an influenza pandemic (Wong and Yuen 2005), and may be more likely to develop in avian influenza than seasonal influenza due to the potentially longer duration of infection by novel viruses. Kiso et al. suggest that "a higher prevalence of resistant viruses should be expected" during a pandemic[17].

The genetic sequence for the neuraminidase enzyme is highly conserved across virus strains. This means that there are relatively few variations, and there is also evidence that variations that do occur tend to be less "fit." Thus, mutations that convey resistance to oseltamivir may also tend to cripple the virus by giving it an otherwise less-functional enzyme. The lack of variation in neuraminidase gives two advantages to oseltamivir and zanamivir, the drugs that target that enzyme. First, these drugs work on a broader spectrum of influenza strains. Second, the development of a robust, resistant virus strain appears to be less likely [7]. It is worth noting that the oseltamivir-resistant strains detected by Kiso et al. all appeared within individual children after treatment with oseltamivir – the children did not catch the resistant strains in human-to-human or bird-to-human transmission [17].

In 2007, Japanese investigators detected neuraminidase-resistant Influenza B virus strains in individuals who had not been treated with these drugs. The prevalence was 1.7%.[21] In 2008, the World Health Organization announced that preliminary results from experiments with Canadian Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 showed that 8 out of 81 samples were resistant to oseltamivir [22].

Pandemic fears

Oseltamivir was widely used during the H5N1 avian influenza epidemic in Southeast Asia in 2005. In response to the epidemic, various governments – including those of the United Kingdom, Canada, United States and Australia – stockpiled quantities of oseltamivir in preparation for a possible pandemic. Though large, the quantities stockpiled would not have been sufficient to protect the entire population of these countries.

In October 2005, the Indian drug company Cipla announced their plan to begin manufacture of generic oseltamivir without license from Roche. Most patent laws allow governments to authorise supply from generic companies, subject to remuneration to patent owners to address public health problems, including emergencies, although Roche has announced its intention to remain the sole supplier of the drug. Cipla argues that it can legally sell oseltamivir to India and 49 other developing countries, possibly as early as January 2006. Also in October, it was announced that Roche was in discussions with four generic drug manufacturers about the possibility of issuing sublicenses to increase production.

In late October 2005, Roche announced that it was suspending shipments to pharmacies in the United States and Canada until the North American seasonal flu outbreak began, to address concerns about private stockpiling and to preserve supplies for seasonal influenza. It said that, when distribution resumes in Canada, the remaining available drug will be saved for use in high-risk settings like long-term care facilities and hospitals. [17][18][19] Sales were suspended in Hong Kong as well, and on November 8, also in China. Roche said it would instead send all supplies to China's health ministry[20].

On November 9, 2005, Vietnam became the first country to be granted permission by Roche to produce a generic version of oseltamivir[21]. The week before, Thai authorities said they would begin producing generic oseltamivir, claiming that Roche had not patented Tamiflu in Thailand[22]. The first Thai generic oseltamivir was produced in February 2006 and are to be available to the public in July 2006[23].

References

- "Roche update on Tamiflu for pandemic influenza preparedness", Roche Media News, 2007-04-26. Retrieved on 2008-02-01. "Tamiflu has now been used in over 50 million influenza patients worldwide"

- Tomoko Otake. "Tragedy swirls around Tamiflu", The Japan Times Online, 2007-03-20. Retrieved on 2008-02-01. "oseltamivir phosphate ... is enormously popular in Japan, where a total of 35 million people have taken it"

- Roche Laboratories, Inc. Tamiflu product information. Last updated Dec. 2005. (Accessed on 20 February, 2006 at http://www.rocheusa.com/products/tamiflu/pi.pdf) – prescribing information document from Roche

- Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- "Tamiflu 'useless' against avian flu", WorldNetDaily, 2005-12-04. Retrieved on 2008-02-01.

- de Jong MD, Thanh, TT, Khanh, TH, Hien, VM, Smith, GJD, Chau, NV, et al. Oseltamivir resistance during treatment of influenza A (H5N1) infection. N Engl J Med 2005;353(25):2667-2672. PMID 16371632 (full text)

- Ward P, Small I, Smith J, Suter P, Dutkowski R. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and its potential for use in the event of an influenza pandemic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55 (Suppl 1): i5-i21. PMID 15709056

- "Double doses of Tamiflu for worst hit nations", 2007-03-29. Retrieved on 2008-02-01.

- "Doctors test double Tamiflu dose to cut H5N1 deaths", Reuters, 2007-03-28.

- Chokephaibulkit, K; Uiprasertkul M, Puthavathana P, Chearskul P, Auewarakul P, Dowell SF, Vanprapar N. (February 2005). "A child with avian influenza A (H5N1) infection.". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 24 (2): 162-166.​

- Hill G, Cihlar T, Oo C, Ho ES, Prior K, Wiltshire H, Barrett J, Liu B, Ward P. The anti-influenza drug oseltamivir exhibits low potential to induce pharmacokinetic drug interactions via renal secretion--correlation of in vivo and in vitro studies. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2002;30(1):13-19. (Online )

- Butler D. Wartime tactic doubles power of scarce bird-flu drug [News article]. Nature2005;438(7064):6. (Accessed on November 2, 2005, at this url)

- Other media reports on neurological side effects in Japan: [1][2][3][4]

- "Links to Tamiflu-Related Incidents in The Japan Times", 2006-11-13.

- "Flu Drug Tamiflu May Cause Odd Behavior in Children", Forbes, 2006-11-13.

- Pediatric Advisory Committee. 2005. Pediatric safety update for Tamiflu. Rockville (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Shiraishi K, Kawakami C, Kimura K, et al. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet 2004;364(9436):759-65. PMID 15337401

- Le Q M, Kiso M, Someya K, Sakai Y T, Nguyen T H, Nguyen K H L, Pham N D, Ngyen H H, Yamada S, Muramoto Y, Horimoto T, Takada A, Goto H, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Kawaoka Y. Avian flu: Isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. Nature2005;437(7062):1108.

- World Health Organization. WHO inter-country-consultation: influenza A/H5N1 in humans in Asia: Manila, Philippines, 6-7 May 2005. (Accessed October 12, 2005, at this url.)

- Moscona, Anne. Oseltamivir Resistance - Disabling Our Influenza Defenses [Perspective]. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;353(25):2633-2636.

- H. Shuji; S. Norio; I. Mutsumi; Y. Masahiko; I. Masataka; K. Kazuhiro; K. Maki; S. Hideaki; K. Chiharu; K. Kazuhiko; M. Keiko; K. Yoshihiro. 2007. Emergence of Influenza B Viruses With Reduced Sensitivity to Neuraminidase Inhibitors. JAMA. 297:1435-1442.

- CTV.ca News Staff. "Tamiflu-resistant flu found in Canada and U.S.", CTV.ca, 2008-02-01. Retrieved on 2008-02-01.

- Macintire, Douglass K. (2006). Treatment of Parvoviral Enteritis. Proceedings of the Western Veterinary Conference. Retrieved on 2007-06-09.

Pollack, Andrew. Is Bird Flu Drug Really So Vexing? Debating the Difficulty of Tamiflu [News article]. The New York Times (Accessed on November 5, 2005 at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/05/business/05tamiflu.html)

- Schwartz, Nelson . Oct 31, 2005. Rumsfeld's growing stake in Tamiflu: Defense Secretary, ex-chairman of flu treatment rights holder, sees portfolio value growing. Fortune (Accessed on Nov 28, 2005 at http://money.cnn.com/2005/10/31/news/newsmakers/fortune_rumsfeld/?cnn=yes)

- Wong, Samson S.Y. and Yuen, Kwok-yung. Avian influenza virus infections in humans. Chest 2006; 129(1):156-168.

- J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 4545-4550. Synthesis of Tamiflu.

- J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 2044-2051. Synthesis of Tamiflu.

- Chimia 2004, 58, 621.

- A Short Enantioselective Pathway for the Synthesis of the Anti-Influenza Neuramidase Inhibitor Oseltamivir from 1,3-Butadiene and Acrylic Acid Ying-Yeung Yeung, Sungwoo Hong, and E. J. Corey J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2006; ASAP Web Release Date: 25-Apr-2006; (Communication) Abstract

See Also:

http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/antiviral.htm --Antiviral Drugs for Seasonal Flu

Molecules of Life Resources

Anti-Viral Drugs

Influenza

- Amantadine-- Symmetrel

- Oseltamivir-- Tamiflu

- Flumadine -- Rimantadine

- Zanamivir -- Relenza

- Peramivir (Rapivab)

- Laninamivir -(Inavir - Japan)

Herpes

Aids

Hepatitis C

- Ribavarin

- Simeprevir (Olysio)

- Harvoni - ledipasvir and sofosbuvir

- Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi)

The Cannabidiol Molecule

Cannabidiol (CBD is the major non-psychoactive component of Cannabis and is being looked at by major drug and consumer companies for various medical and social uses.